Today and every day, I am a white person who advocates for the fair and equal treatment of BIPOC (Black, Indigenous People of Color) and anyone living without the same privileges my cisgender heterosexual white skin affords me.

Today’s story is one that happened back in the summer of 2020, in the wake of the petitioning, protesting, and rioting happening across the globe in response to the murder of George Floyd and the ongoing and senseless killing of Black people at the hands of law enforcement.

If you know me, and/or you’ve been following my posts and stories, then you know that my husband of 28 years, Shederal, and our two sons, Jalan and Devan, are Black. As the mother of two young Black men—Jalan is 23 and Devan is 21—I am continually engaging in conversations to remind them to stay safe, to remain vigilant, and to remember what they should and should not say or do if they encounter law enforcement. These conversations wouldn’t even be necessary if my sons were white, but as they are Black there are special considerations to make just in order for them to remain safe and not be arrested, or worse, killed.

As I have learned over the years, staying vigilant is an everyday way of life for Black people, and there are so many things Black people cannot do openly, freely, and without conscious consideration that white people can, especially here in the South. As a white woman, having to be fearful of my life and fight for basic human rights are not things that naturally and perpetually remain on my radar. My skin color affords me privilege and access. As I live with Black men, my radar is packed with everything that might hurt them because of “living while being Black.”

Since moving back to Georgia from Florida in 2016, I’ve kept a “smile jar.” It started out on my kitchen counter, and now it sits on my desk. This jar is your average hinge-topped glass jar, the kind that brings to mind pickles or preserves or moonshine (depending on your grandmother and her hobbies). My goal for the smile jar was to capture small mementos of the people, places, and activities that bring me joy throughout the year and drop them inside. At the end of each year since then, on New Year’s Eve, I’ve emptied the jar and reminisced about all the events that made me smile: Shederal’s Old School Basketball League ticket stubs, Jalan’s art show programs, Devan’s football game ticket stubs, a playbill from a stage show, Disney World wristbands, and other meaningful ephemera.

At the start of 2020, as per usual the smile jar was empty. When our 14-year-old pit bull (my youngest baby), Rocco, injured his back in January of that year, and I had to help him walk, help him use the bathroom, help him with everything, the jar remained empty. When he died in February, there was still nothing to add. When news of COVID-19’s elevation to a global pandemic and the subsequent quarantine started in March, I was too focused on keeping my family safe and healthy that the jar was the farthest thing from my radar. Summer of that year, I was packing my kitchen to move—yeah, moving during a pandemic was NOT fun, but we didn’t have any choice. That’s an entirely different story for another day, and I digress—when I finally noticed the smile jar again. Midyear was a time when the thing was normally halfway full, but it was still empty. Or so I thought...

While packing dishes, my eyes caught onto the smile jar. There was something hot pink inside. I dried my hands and opened the hinged lid.

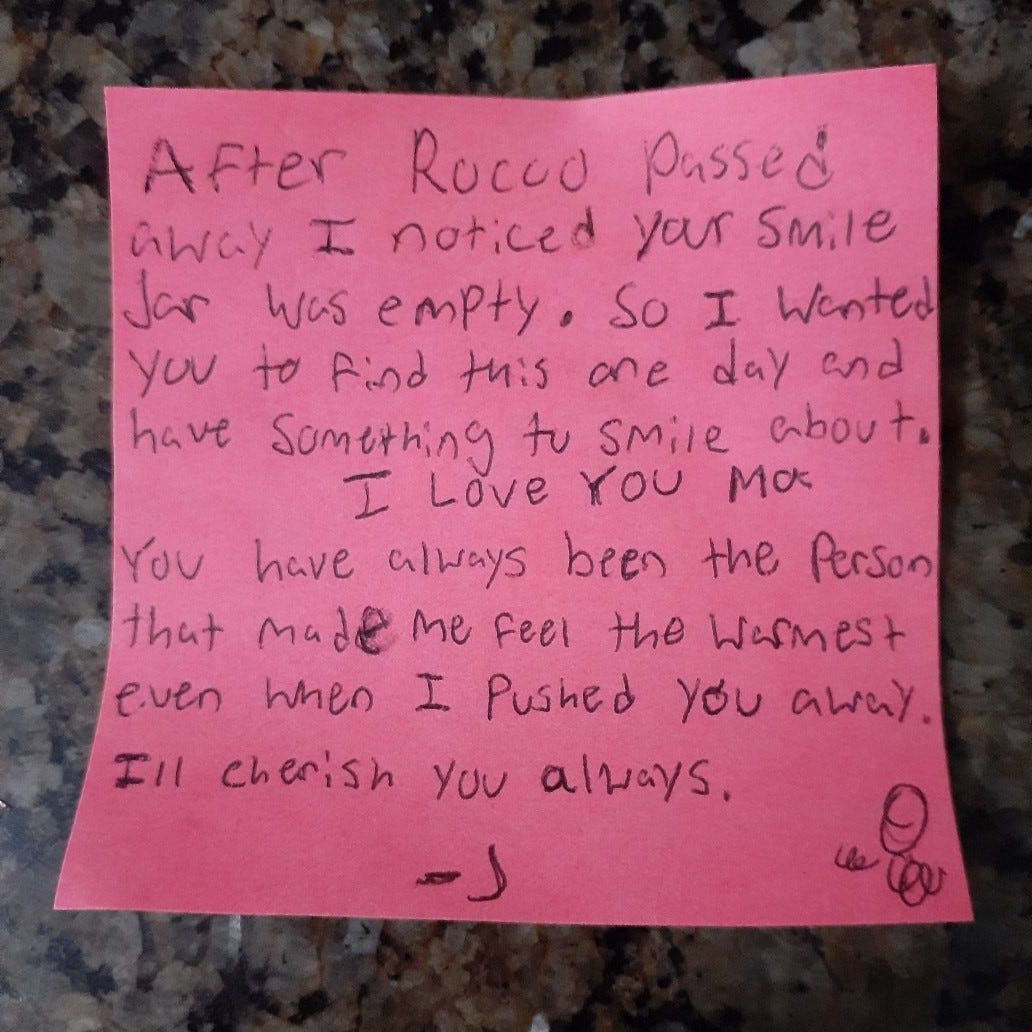

A Post-it note was leaning against the wall of the jar, Jalan’s handwriting scrawled across it. Here’s what it read:

After Rocco passed away I noticed your Smile Jar was empty. So I wanted you to find this one day and have something to smile about. I LOVE YOU Ma. You have always been the person that made me feel the warmest even when I pushed you away. I’ll cherish you always. - J

If you’re a good parent, you’re naturally proud of your kids and a note like this one from Jalan is enough to fill 10,000 smile jars. If you’re the parent of Black men, you’re fearful every single day of your life that something will happen to them and you won’t ever get these little notes again, you won’t ever argue with them again over things they think they can do because they are “grown,” (which my sons love to remind me) like wearing their hoodie pulled up over their heads when walking into a store or down the street or anywhere, for that matter. You watch what happens to Black men like George Floyd and when you hear them call out for their mamas as they are being murdered by the same men who are sworn to protect them, you hear your own son’s voice calling out for you. Every single time Shederal and the boys walk out the front door, I light a candle and say a quick prayer of protection over them. Parents of white kids don’t have to even consider the thought that their family may not return home “simply” because of their skin color, but according to Shederal and all my Black loved ones, being Black is not simple at all.

In an attempt to try and stitch some joy around the quarantine situation, that summer I started promoting things that bring me joy—things like my surprise smile jar note from Jalan—and encouraging others to do the same. But, during that time, while White America muted our own Instagram stories with our own agendas, and instead started sharing Black stories and promoting the works of Black artists and writers, a few thoughts occurred to me: I cannot imagine how difficult it must be some days for Black people to seek and find joy. I cannot imagine the stories attached to the things with which Black people might fill their own smile jars. And I can only imagine how exhausting it must be for Black people to find and hold onto joy given the fact that every day is a day of fighting for basic human rights.

I could go on and on about all the things that, as a white woman, I do not understand and all the ways in which I want so badly to be helpful and supportive of the Black community, but that won’t help. Words won’t help. They fall flat. But what I can do, what I do every day of my small but privileged life, is love and protect my Black family and friends. I can take action on their behalf. I can share their stories, raise their voices. I can advocate for equality and use my privileges to help advance those I love so much. I can help educate other white people and in some small way—and please forgive me if this comes across as naïve or cliché—maybe I can even help promote change.

I will conclude this story with a couple of questions to ponder:

What joyful ephemera would you add to a smile jar of your own?

My fellow white readers, how are you using your privileges to help advocate for equality for all?

In her more than thirty years as a storyteller and visual designer, Amanda “Mandy” Hughes has written and designed over a dozen works of literary, Southern Gothic, and women’s fiction under pen names A. Lee Hughes and Mandy Lee.

Mandy is the founder of Haint Blue Creative®, a space for readers and storytellers to explore, learn, and create. She holds a Bachelor and Master of Science in Psychology, and she has worked as an instructional designer for nearly twenty years.

When she’s not writing, Mandy enjoys the movies, theater, music, traveling, nature walks, birdwatching, and binging The Office. She is a tarot enthusiast who uses the cards to enhance creativity and foster wellness. She lives in Georgia with her husband and four sons, two of whom are furrier than the others (but not by much). Visit her website at haintbluecreative.com and follow her on Instagram @haintbluecreative.

My partner is black but ironically I’m the one who has experienced police brutality. But the abuse and racism/homophobia she experienced at her job and now her employer blocking her unemployment is so infuriating. I have no problem being the “aggressive rude white “woman” for her. I network for her and protest. I consider myself her protector and protecting her family too through my own advocacy, privilege and SpellWork.

What a beautiful piece! You and your work are treasures! 💖